A triathlete’s VO2max number can be a good basis for bragging rights in the endurance sports arena. If you know this number, which defines your maximum aerobic capacity, and it’s a good number, you can talk trash while hanging at the pool edge, chatting in spin class or stretching on the track.

A triathlete’s VO2max number can be a good basis for bragging rights in the endurance sports arena. If you know this number, which defines your maximum aerobic capacity, and it’s a good number, you can talk trash while hanging at the pool edge, chatting in spin class or stretching on the track.

But as a measurement that originated in the second century with Greek physicians blowing into sheep bladders, is the VO2max really that valuable?

I’ve had a VO2max test each of the past three seasons. This year I had the test performed on both a treadmill and an electrically-braked cycle ergometer. My reasoning for testing has been to establish my training zones and particularly my AT (Anaerobic Threshold).

My goal as a Triathlete is to continue to improve, and unlike the professional athlete, I have a limited amount of time to train so I need to make sure that I get the most out of every workout. To me, improving means being able to swim, bike, and run faster for a longer duration.

I’ve been lucky and over the past few years have had some very knowledgeable Group Fitness Instructors at Lifetime Fitness. I’ve also spent time reading and researching a variety of training methodologies for endurance athletes. I wish I can tell you that I have found some magic formula but I haven’t.

What I have learned is that at some point when increasing intensity during exercise, your body switches from burning fat as the primary source of energy to burning primarily carbohydrates. This point is referred to as your AT or Anaerobic Threshold. Why is this important? Well, I’m glad you asked. The average human body can only store about 1500 to 2000 calories of carbohydrate where as it can store upwards of 30,000 calories of fat. Even the leanest of endurance athletes have a nearly limitless supply of fat calories.

What I have learned is that at some point when increasing intensity during exercise, your body switches from burning fat as the primary source of energy to burning primarily carbohydrates. This point is referred to as your AT or Anaerobic Threshold. Why is this important? Well, I’m glad you asked. The average human body can only store about 1500 to 2000 calories of carbohydrate where as it can store upwards of 30,000 calories of fat. Even the leanest of endurance athletes have a nearly limitless supply of fat calories.

AT is also the point at which you begin to notice marked fatigue, and this marks the beginning of the end. Your muscles will soon lose the ability to maintain that intensity and you will either have to slow down, to an intensity below your anaerobic threshold, or stop.

To achieve our overall goal to swim, bike, and run faster / longer we must train our bodies to work at ever increasing levels of intensity for longer periods of time below AT.

Therefore, accurately knowing your AT is pretty important to your training.

Therefore, accurately knowing your AT is pretty important to your training.

There are several methods of determining your AT. A very simple method for estimating the anaerobic threshold is to assume anaerobic threshold occurs at 85-90% maximum heart rate (220-age). Unfortunately heart rate varies greatly between individuals and even within the same individual so this is not a very reliable test.

For the more experienced athlete, a time trial of a 10km run or 30km cycle at or close to anaerobic threshold can be used to determine AT. By simulating a race in training and recording heart rate, the anaerobic threshold may be determined. Alternatively, exercising for 30 minutes at the fastest sustainable pace can be used. The key is to sustain a steady pace which is why this test is more suited to experienced athletes who can gauge how fast to set off. A heart rate monitor with split time facility is required to record heart rate at each 1-minute interval. Take the average heart rate over the final 20 minutes as the heart rate corresponding to anaerobic threshold.

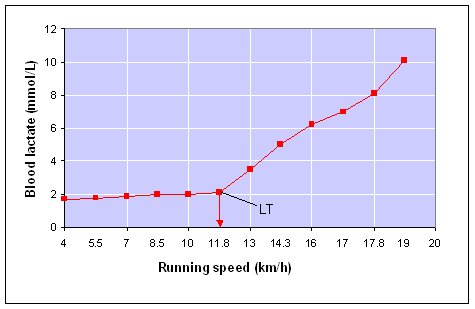

The most accurate way to determine lactate threshold is via a graded exercise test in a laboratory setting (1). During the test the velocity or resistance on a treadmill, cycle ergometer or rowing ergometer is increased at regular intervals (i.e. every 1min, 3min or 4min) and blood samples are taken at each increment. Very often VO2 max, maximum heart rate and other physiological kinetics are measured during the same test (2). Blood lactate is then plotted against each workload interval to give a lactate performance curve. Heart rate is also usually recorded at each interval often with a more accurate electrocardiogram as opposed to a standard heart rate monitor.

The most accurate way to determine lactate threshold is via a graded exercise test in a laboratory setting (1). During the test the velocity or resistance on a treadmill, cycle ergometer or rowing ergometer is increased at regular intervals (i.e. every 1min, 3min or 4min) and blood samples are taken at each increment. Very often VO2 max, maximum heart rate and other physiological kinetics are measured during the same test (2). Blood lactate is then plotted against each workload interval to give a lactate performance curve. Heart rate is also usually recorded at each interval often with a more accurate electrocardiogram as opposed to a standard heart rate monitor.

Once the lactate curve has been plotted, the anaerobic threshold can be determined. A sudden or sharp rise in the curve above base level is said to indicate the anaerobic threshold. However, from a practical perspective this sudden rise or inflection is often difficult to pinpointSo the bottom line is that whichever method you chose will have some inherit flaws. Personally, my lab results have not corresponded to the data I’ve collected from race day and time-trails. In fact the lab results are significantly different and are of no practical use for training. For me, recording my heart rate during race conditions at near maximal efforts has produced the most reliable results. This race day data seems to correspond to what I perceive to be AT. Since my lab results have been suspect I’ll continue to use a combination of time-trial and perceived exertion to determine my Anaerobic Threshold for training purposes.

References

1) McArdle WD, Katch FI and Katch VL. (2000) Essentials of Exercise Physiology: 2nd Edition Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

2) Maud PJ and Foster C (eds.). (1995) Physiological Assessment Of Human Fitness. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics